Why Sanctions Fail

Direct military force has for centuries been the principal means for States to achieve ambitious foreign policy objectives, whether seizing or defending territory, altering a state’s military behaviour or reshaping its internal political and economic structures. Since the First World War and the rampant development and consolidation of world financial markets a shift in attention towards non-violent economic force has developed to an extent which has forged a set of coercive measures surpassing direct military force as the principal mode of engagement; at the apex of contemporary economic warfare, sanctions serve as our post-war world's enlightened alternative to open conquest and bloodshed, a humane and non-violent mechanism for the ends of global norms, the ‘rule of law’, force which compels rather than openly subdues antagonists. The mark of a civilised country, it seems, is aversion to open conflict and a commitment to ‘quieter’ approaches to dominance. Over the past century international relations scholarship has championed the utility of sanctions, casting them as indispensable tools in the arsenal of statecraft, a mark of progress and the refinement of geopolitical engagement. This intellectual edifice has no doubt served to lend relative credence to the recent wave of punitive measures levied by the UK, US, and allied governments against the Russians following their invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Economic warfare is of course ancient, but our present method of sanctions traces its origins to the interwar period in Europe, when the League of Nations sought to harness economic coercion as a means of enforcing a premature form of collective security during the rise of openly militarist ‘trenchocratic’ European leaders. Sanctions imposed on Italy during the 1935 invasion of Ethiopia marked one of the earliest attempts to deploy such measures in lieu of direct military engagement. While these efforts failed to halt Italian aggression, they laid the groundwork for the widespread adoption of sanctions in the post-war international order. The United Nations further refined the art of sanction; in theory, sanctions were to be wielded collectively, targeting states that violated international law. In practice their deployment became increasingly unilateral, driven by the strategic interests of the United States and its increasingly vassalised strategic partner, Great Britain. With unrivalled command over the newly codified global financial architecture following the Bretton Woods accords, the US asserted itself as the preeminent enforcer of sanctions, the sole guarantor of a worldwide regime of Human Rights and International Security (only further ingrained after the decomposition of Bretton Woods, followed by the collapse of the singular counter-weight to US geopolitical interests, the Soviet Union, a mere two decades after).

Whether the objective is regime change, policy reversal, or containment, sanctions have consistently fallen short. Their failure stems from a miscalculation, the belief that forced economic hardship will translate into political pressure sufficient to compel either the citizenry of the enemy state into open revolt, or the state itself into negotiation and compliance with ‘global norms’. The decades-long embargo on Cuba has neither toppled its government nor facilitated the liberalisation of its economy. Certainly these measures have worsened Cuban quality of life, reducing the availability of goods, humanitarian items such as medicine, and so on, but their State and their citizens in the main refuse to shift toward concurrence with American foreign policy objectives. In Iran sanctions have largely crippled the economy, causing skyrocketing inflation, unemployment, and shortages of basic commodities, however the only slight murmur of dissent against the regime come counterintuitively from those least affected in Iranian society, from a markedly fringe element amongst the metropolitan middle classes in Tehran. In the case of North Korea which has been subjected to the most stringent barrage of sanctions in history, these measures have left the Kim government's nuclear ambitions unaffected, serving instead to isolate the country from global markets. The result of US-led sanctions inflicting immense suffering on the North Korean people in the short term has by all accounts only strengthened Kim's mandate and his popular reception in the country, understood to be the only line of defence against foreign aggressors, contributing to ever greater levels of North Korean patriotic fervour and regime stability. A further consequence is an ever stronger and more emboldened North Korean military, now reportedly assisting fellow Western-sanctioned partners like Russia in its military engagements, an alliance unlikely to break any time soon.

Even in cases where it can be argued sanctions have been successful, the costs have outweighed the benefits for the states which enforce them. The imposition of sanctions on Russia since the beginning of its Special Military Operation, heralded as the linchpin of Western efforts to punish and isolate the Kremlin, have neither crippled the Russian state nor significantly effected its strategic calculus, but rather emboldened it, all the while forcing Europe and the rest of the world to bare the consequences.

When the US and its allies unleashed a torrent of sanctions on Russia in early 2022, the goal was clear: to deliver a swift blow to its economy, force a recalibration of its military ambitions, and demonstrate the punitive might of the liberal international order; to force a repetition of the Yeltsin event, however in a far more oblique manner. This strategy hinged on the assumption that severing Russia from SWIFT and other global financial mechanisms, restricting access to critical technologies, crippling its energy exports, and so on would render its economy inert; the outcome was to be the near complete reverse of Western expectations. The initial shock of sanctions, marked by a rapid depreciation of the Rouble and a correspondingly sharp decline in quality of life, gave way to a rapid recovery. James K. Galbraith, economist, stated in regard to the attempt to break Russia's economy wasn't just a failure, but entirely backfired on the instigators:

...they were imposed by one important sector of the world economy which then cut itself off from resources that it needs – and that’s particularly true of Western Europe – in return for cutting Russia off from various things that Russia doesn’t really need.

The departure of Western firms from Russia unfolded on terms that profoundly reshaped the global economic landscape in Moscow’s favour. For those exiting permanently, the conditions of departure were strikingly advantageous to Russian interests. By the West forcing itself to sever all ties, Russia was able to break from a decades-long false dependency on Western firms and supply chains; Companies were compelled to sell their capital assets – factories, machinery and other infrastructure – to Russian businesses at steeply discounted prices. These acquisitions were facilitated by loans from Russian banks or alternative financial mechanisms, effectively transferring substantial capital wealth from Western ownership into Russian domestic hands — what was intended as a punitive measure became a windfall for Russian industry. Russia emerged with a leaner, more self-reliant economy, uniquely positioned to leverage its abundant natural resources and unscathed Easterly-facing continental supply chains against a Europe reeling from its subservience to American objectives, made especially embarrassing following the ascension of a decidedly hostile Trump administration where the further continuity of the Western alliance has been made an open question. Against a Europe crippled by soaring energy prices, Russia enjoys an economic climate characterised by relatively low resource costs, a strengthened Rouble, and the sovereign capacity to siphon its own natural resources to maintain and lower its domestic energy prices, while still maintaining military operations and making steady gains in Ukraine.

Ultimately sanctions have achieved what the Russian government itself would have been unwilling and unable to without them: Prior to the sanctions, Moscow was not in a position to compel Western businesses to abandon their investments or force Russian oligarchs to break with Western-controlled financial mechanisms. Such sovereigntist measures, politically fraught and economically risky, were neither desired nor feasible. Nevertheless, through the sanctions, the West imposed precisely these outcomes, compelling a rupture that inadvertently fortified the economic sovereignty of their enemy. Enormous space was pried open for domestic industries to flourish, further insulating the economy from external shocks. Principally the sanctions have reorientated Russia’s economic trajectory, enabling it to pivot towards new markets and deepen partnerships with other rivals to US hegemony.

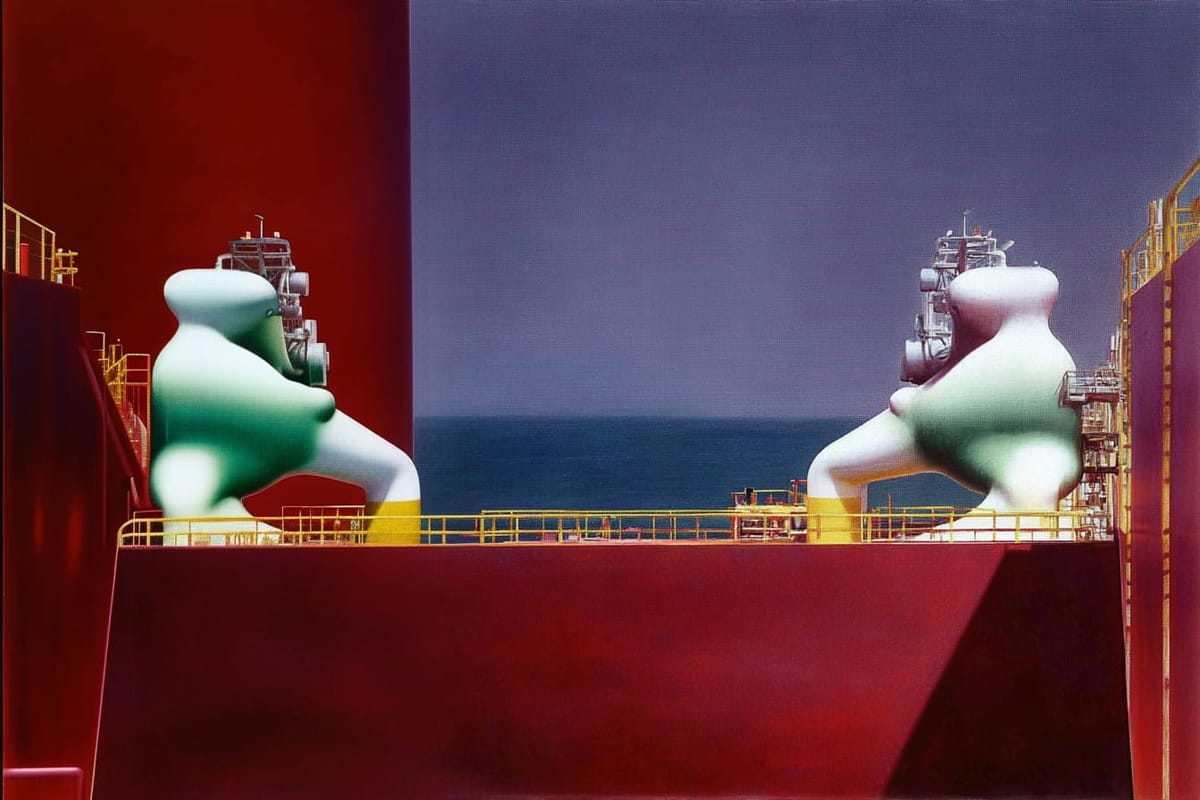

In light of this reality the European Union has quietly circumvented its own sanctions to access Russian gas through indirect means. Rather than total severance, the flow of Russian energy into European markets continues; rerouted via intermediary nations, creating a labyrinth of transactions designed to obscure the original source, ghost stories fill the headlines of vast ‘shadow fleets’ under strange flags roaming continental waters, declaring erroneous coordinates to obscure their true intentions, ghosts in the supply chain being impotently ‘warded off’ by Brussels. Turkey and Kazakhstan have emerged as pivotal middlemen, purchasing Russian gas and subsequently selling it to Europe, often at inflated prices for the complexity of added layers of obfuscation. Liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports from Russia have similarly found their way into European ports under the guise of shipments originating from neutral or ostensibly compliant states. According to an article by the Financial Times, “phasing out Russian gas is a central policy aim of the European Commission. However, its target to reduce the EU’s use of Russian fossil fuels to zero by 2027 has been thrown off course by an increase in imports of Russian LNG, most supplied from Yamal.” This spectral network underscores the strategic imperative of Russian energy, which remains integral to Europe’s industrial output and heating needs after decades of forced deindustrialisation and hollowing-out of Europe’s energy and manufacturing base.

The unintended consequences of sanctions extend beyond the reshuffling of assets and ownership within Russia; they continue to fundamentally alter geoeconomic relations in ways that run far ahead of any expectation. As Europe scrambles to secure alternative energy supplies, Russia has redirected its vast reserves of oil and gas towards Asia, solidifying powerful trade alliances with the rising powers of the East, all the while maintaining covert relations with European states and private companies dodging what German Bundestag member and BSW leader Sahra Wagenknecht describes as a “killer program” against European and German companies. Wagenknecht, a veteran German parliamentarian, has risen significantly in popularity since the start of the Ukraine war asserting the “irrationality” of German and EU compliance with US-led sanctions, proposing Germans must “simply… tie our energy imports with the criteria of the lowest price and not any kind of double standards or ideology.” These statements have been echoed by Slovakian premier Fico, who derided Kiev’s decision to block Russian fuel imports, stating the non-EU state had no right to block imports and destabilise a Bloc it is not a member of. Meanwhile the sudden breakdown of Russia’s long-term agreements with European states has simply compounded and deepened its relationship with other states. This pivot has not only diversified Russia’s energy exports, but entrenched its role as a key supplier of energy in a rapidly shifting global order.

Paradoxically, sanctions have proved not to cripple the West’s antagonists but embolden them, accelerating a major renegotiation of the dynamics of world trade, revealing wrought contradictions at the centre of our global economic order. The record demonstrates a persistent pattern: sanctions frequently exacerbate humanitarian crises, inflict suffering on civilian populations, all the while failing to achieve their intended political and economic ambitions. Rather than reinforcing the post-Cold War US-led order, the US, UK, and Europe have helped facilitate new alliances, restructuring global financial and geopolitical architecture against themselves. In the West’s failed attempt to scupper Russian ambitions, the price we ultimately pay as Westerners is with our own sovereignty and economic security. For Western powers to save face, they first ought to realise the limits of their ability to play hegemon; second, renegotiation must take place between the West and Russia while there remains a shred of good will, and at least the semblance of a hand to play. Britain’s place in the rising global economic and collective security architecture must remain an open question, lest we lose everything for the pursuit of another country’s lost and irrational cause.